Traditional Cherokee culture viewed the sun as women and the moon as men. This symbolism reflected their belief in gender balance that helped them survive. Cherokee women held much power in their society, unlike European patriarchal systems. Their power came from tracking family lines through mothers, which gave women complete control of households and farming.

Cherokee women ran all farming activities on their own, while men hunted and traded. This 700-year old system faced its first real test when Europeans arrived. The deerskin trade marked their first contact with European settlers, and then it changed how men and women worked and earned. Cherokee women showed they could adapt well by using European iron tools in their farming. Their political power slowly decreased as male warriors gained more importance, but they managed to keep their control over farming and raising animals. Theda Perdue’s research reveals how Cherokee women knew how to protect their traditions while adjusting to outside pressures between 1700-1835.

Colonial Narratives and the Erasure of Cherokee Women

Image Source: Muskrat Magazine

Cherokee women vanished from early European historical records through systematic erasure. A Cherokee leader named Attakullakulla traveled to South Carolina in 1757 to negotiate trade agreements. He asked a striking question about the absence of white women at the council: “Since the white man as well as the red was born of woman, did not the white man admit women to their council?”. The governor struggled and needed several days to develop a response.

Europeans failed to grasp Cherokee gender structures. They saw Cherokee women as “promiscuous drudges” who worked for men they thought were lazy. Amerigo Vespucci’s letters spread harmful stereotypes. He described Native women as “lustful” with “tolerably beautiful bodies” who “defiled and prostituted themselves”. These descriptions showed how Europeans couldn’t understand gender roles different from their patriarchal system.

Missionaries twisted Cherokee women’s real-life experiences even further. Missionary Daniel Butrick complained in 1840 about Cherokee women who used “profane language” or “attended dances”. He also “forbade any student in his school to go to a ball play or an all night dance”. These missionaries reshaped Cherokee gender roles by forcing Euro-American values of “true womanhood”.

Researchers face their biggest challenge with the historical record. Indigenous women remain largely absent from historical narratives, even thirty years after Ella Cara Deloria’s groundbreaking work “Waterlily”. Ann McGrath points out that colonialism’s basic contours claimed Indigenous peoples “could have no history” and Indigenous women were especially “expunged from history”.

Ethnohistorians now use different methods to uncover Cherokee women’s voices. Theda Perdue uses “upstreaming” to trace cultural patterns from today to light up this “shadowy history”. Modern scholars increasingly show how Cherokee women kept their agency during this period. They challenge the divide between “traditional” and “modern” that puts Indigenous women outside modern history.

Cherokee women lost their political voice as the government became centralized. The 1827 Cherokee Constitution followed the U.S. Constitution’s model. This change stripped Cherokee women’s right to vote or hold public office. The constitutional convention’s law stated clearly: “No person but a free male citizen who is full grown shall be entitled to vote”.

Ethnohistorical Reconstruction of Cherokee Gender Roles

“The council meetings at which decisions were made were open to everyone including women. Women participated actively. Sometimes they urged the men to go to war to avenge an earlier enemy attack. At other times they advised peace. Occasionally women even fought in battles beside the men. The Cherokees called these women ‘War Women’, and all the people respected and honored them for their bravery.” — Theda Perdue, Professor of History, University of North Carolina; leading scholar on Cherokee and Native American women’s history

Archeological findings and historical records show how Cherokee society gave women remarkable power. Their social structure followed a matrilineal system that traced family lines through mothers instead of fathers. The children belonged to their mother’s clan, which made their maternal uncle their most influential male figure.

Cherokee women owned the family homes. Their husbands moved in with them after marriage. When relationships ended, men went back to their mothers’ homes while children stayed with their mothers. This setup gave women freedom to end marriages without social consequences.

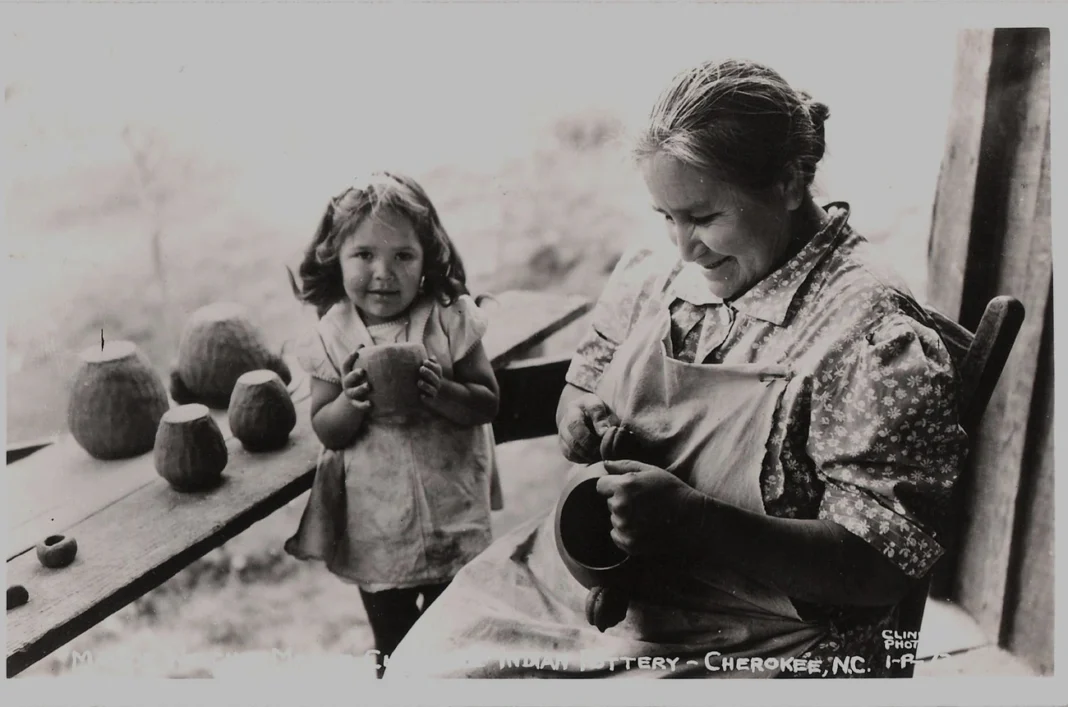

Women’s power came from their role in agriculture. They grew corn, beans, squash, sunflowers, and pumpkins that fed the entire society. The tribe gathered each September to honor Selu, the Corn Mother. This celebration showed how much they valued women’s role in keeping their community alive.

Cherokee women played active roles in politics too. They attended council meetings and spoke up about war and peace decisions. Some women fought in battles with men and earned respect as “War Women.”

The Coweeta Creek site discoveries back up these historical accounts. Women were buried close to homes with special items like turtle shell rattles and shell beads. These burial goods showed their connection to household and clan leadership.

Cherokee views on gender were quite different from European ideas. Men and women had sexual freedom and married because they liked each other, not for money or status. They saw consensual relationships as natural parts of life.

This balanced system helped the Cherokee adapt to changes while keeping their culture intact. Scholar Theda Perdue points out that by sticking to their traditional gender roles, Cherokee people successfully took up new industries without losing their social structure. Women became champions of cultural preservation during these challenging times rather than victims of colonial change.

Persistence and Adaptation in the Face of Cultural Disruption

Image Source: United Cherokee Nation of Indians~Aniyvwiya

Cherokee women endured three major historical upheavals during the 18th and 19th centuries. They lost their ancestral lands, lived through the Civil War, and saw their territories divided through allotment. These events forced them to radically redefine gender roles in Cherokee society. Despite these challenges, they found ways to keep their traditional ceremonies and beliefs alive.

The U.S. government introduced its “Civilization Policy” in 1840 to assimilate and “modernize” indigenous people. This policy specifically targeted gender roles. Cherokee women received industrial tools like spinning wheels and metal sewing needles, which they saw as tools for progress. Their traditional farming roles gradually shifted to plantation workers, slaves, and men as women moved toward indoor industrial work. Women’s power as matriarchs declined because they no longer managed the farmlands.

Cherokee women stood firm against these changes. They sent a petition to tribal leaders in 1817 opposing land cessions. “We have raised all of you on the land which we now have, which God gave us to inhabit and raise provisions,” they wrote. They reminded their male counterparts of women’s traditional authority: “Your mothers, your sisters, ask and beg of you not to part with any more of our land.” This petition showed how women fought to protect gender balance while adapting to outside pressures.

The Cherokee Constitution of 1827 stripped women of their right to vote or hold public office. This significant loss of political power happened alongside the adoption of Euro-American ideals of “true womanhood” that restricted women to domestic duties. Cherokee women’s unified understanding of their identity fractured by the end of the 18th century.

Legal changes weakened clan power and reduced women’s independence, yet Cherokee women’s story remains one of endurance. Their influence resurfaced in 1985 when Wilma Mankiller became Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. Joyce Dugan’s election as Principal Chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokees followed. These leadership roles showed that Cherokee women’s influence remained strong despite generations of cultural disruption.

Cherokee women’s historical role tells a powerful story that challenges traditional colonial accounts. These women managed to keep their cultural continuity through matrilineal authority despite relentless external pressures between 1700-1835. They showed remarkable agency as tradition’s guardians while carefully choosing beneficial European innovations to adopt.

European observers completely misread Cherokee gender dynamics, as historical records show. They couldn’t grasp gender systems that differed from their patriarchal European norms, which led to substantial distortions in historical accounts. Learning about authentic Cherokee women’s experiences now requires new methods and careful study of archeological evidence along with written records.

Cherokee women used strategic adaptation during waves of cultural disruption. The “Civilization Policy” and constitutional changes reduced their formal political power. All the same, they passed cultural knowledge down through generations. Their petition against land cessions proves their continued resistance and cultural awareness even as political structures shifted around them.

Cherokee gender dynamics prove that Indigenous societies were neither purely “traditional” nor “integrated.” These women’s experiences show a complex balance of identity and power throughout colonization. Women leaders like Wilma Mankiller and Joyce Dugan emerged again later, which shows how deeply female leadership was rooted in Cherokee cultural memory despite generations of suppression.

Cherokee women’s story is not just an interesting historical detail but fundamentally challenges dominant historical narratives. They kept their cultural bonds strong despite tremendous pressure. This reminds scholars and readers that Native American history has nowhere near the simplicity that colonial accounts suggest. Their historical record emphasizes the resilience of Cherokee women who protected their culture’s core even as circumstances forced them to adapt.