Global displacement numbers hit a record high in 2020, with 82.4 million people forced to leave their homes worldwide. This massive number shows just one part of a complex worldwide issue that has grown from a local policy concern into a global challenge with deep consequences. Migration patterns are changing the power balance between countries by a lot and challenge our traditional understanding of sovereignty and citizenship.

International migration’s effects reach way beyond the reach and influence of simple population movements. Migrants sent $550 billion back home, and this is a big deal as it means that public development funds and helps reduce poverty in their home countries. Different regions show varying patterns of migration flows, as recent reports highlight. The refugee crisis of 2015 brought 1.2 million refugees to Europe and completely changed European Union policies and international partnerships. Migration data also shows about 13 million people without any citizenship worldwide, which shows how citizenship keeps evolving as people become more mobile.

This piece gets into how migration affects international relations through hidden power dynamics, from border control outsourcing to diaspora diplomacy. While organizations like UNDESA provide frameworks to define international migration, new challenges like climate-driven displacement create fresh categories of “climate refugees.” These changes make traditional governance methods more complex and reveal shifting power structures globally.

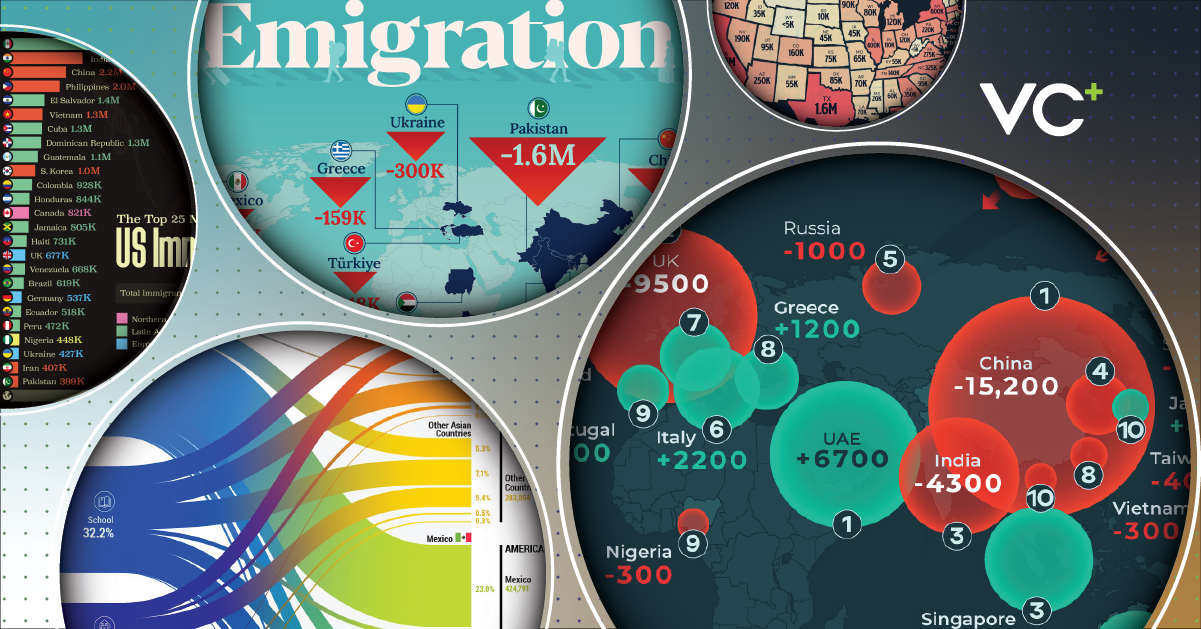

Global Trends in International Migration Since the 1990s

Image Source: Visual Capitalist

People’s movement around the world has changed a lot since the 1990s. The number of international migrants has grown from 154 million in 1990 to 304 million in 2024. These numbers look big, but international migrants make up only 3.7% of the world’s population in 2024, up slightly from 2.9% in 1990.

Net International Migration Patterns by Region (2023 UN Data)

International migrants spread differently across regions worldwide. Europe and Asia lead with about 87 million and 86 million international migrants. Together they make up 61% of all global migrants. North America comes next with almost 59 million international migrants, which is 21% of the world’s migrant population.

Oceania stands out with the highest percentage of international migrants compared to its population size. The numbers tell an interesting story: international migrants make up 21.4% of Oceania’s population, while North America has 15.7% and Europe has 11.6%. Asia and Africa show much lower numbers at 1.8% and 1.9%.

Gulf Cooperation Council countries show remarkable figures:

- United Arab Emirates: 88.4% of people living there were born in other countries

- Qatar: 75.7% of residents come from other countries

- Kuwait: 73.6% of the population comes from elsewhere

Africa’s migrant numbers grew from 15.7 million in 1990 to 25.4 million in 2020. Yet the percentage dropped from 2.5% to 1.9% during this time. Population growth in Africa outpaced migration.

South-South vs South-North Migration Flows

Most people think migrants mainly move from developing to developed nations. The reality differs. South-South migration leads the way with 37% of all international movements. South-North migration follows at 35%.

South-South migration has evolved over the years. It led international migration in 1990, briefly lost the top spot to South-North migration in 2005, and regained its position by 2020. Countries in the Global South now host 85% of refugees.

The facts challenge what many believe about where migrants go. Take West Africa as an example – 64% of migrants stay within West Africa rather than moving to Europe or North America. Northern Africa stands alone as the only African region where more people leave for other areas, mainly heading to the Middle East instead of Europe.

Gender and Age Demographics in Global Migration

Migration patterns show interesting gender shifts since 1990. Women made up 49.4% of international migrants in 2000, but this dropped to 48.1% by 2020. The difference between female and male migrants grew from 1.2 percentage points in 2000 to 3.8 percentage points in 2020. This shows migration becoming slightly more male-dominated.

Different regions show varied gender patterns. Women make up most international migrants in Europe and North America at 52.4% and 51.2%. Asia tells a different story with female migrants at only 42%.

Some migration routes show big gender differences. Gulf Cooperation Council countries have stark contrasts – male migrants make up 83% of all migrant workers in Arab States. This happens because jobs split along gender lines, with men taking most construction and security work in Gulf States.

Work-related migration creates both worldwide gender gaps and regional differences in migration patterns. Migrant workers made up 62% of international migrants in 2019. The numbers break down to 99 million males (58.5%) and 70 million females (41.5%), creating a gap of 29 million. These patterns show how job markets divided by gender shape migration worldwide.

Legal Frameworks and Definitions in Migration Governance

Legal definitions and frameworks determine rights, responsibilities, and protections for people on the move. These elements shape international migration governance. The frameworks specify who qualifies for specific types of protection, what circumstances apply, and what obligations states have toward different migrant categories.

International Migration Definition under UNDESA

The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) created the original definition of international migrants through its 1998 Recommendations on Statistics of International Migration. This definition states that an international migrant is “any person who changes his or her country of usual residence.” Long-term migrants change their usual residence for at least one year, while short-term migrants move between three months and one year.

An international migrant’s characteristics include residence, citizenship, duration of stay, purpose of stay, and place of birth. These elements are the foundations of migration data collection and analysis. Countries don’t always apply this definition consistently, and some use different minimum residence durations or other criteria that make national statistics harder to compare.

Citizenship defines the legal bond between individuals and their state, and plays a vital role in migration governance. This bond determines an individual’s right to enter and live in a given state. Countries distinguish between nationals (the country’s citizens) and foreigners (people without the country’s citizenship).

The 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol

The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees stands as the life-blood of international refugee protection. World War II displacement prompted its development, and it offers the most detailed codification of refugee rights internationally. Article 1 defines a refugee as someone who, “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion,” lives outside their nationality’s country and cannot or won’t return.

The Convention had two substantial limitations at first. The rules applied only to refugees “as a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951.” States could also choose whether these events applied only to Europe or worldwide.

The 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees eliminated both time and geographic restrictions. Refugee flows from decolonization made this expansion necessary. The Protocol allowed the Convention’s universal application, making it relevant to refugee situations after 1951.

Today, 145 states have ratified the 1951 Convention and agreed to follow its rules. All but one of these states—the Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, Monaco, and Turkey—chose to keep the geographic restriction to Europe. Congo and Monaco later removed this restriction, but Turkey kept it while Madagascar hasn’t ratified the Protocol.

Legal Gaps in Climate-Induced Displacement

People displaced by climate change face a substantial legal protection gap. Media and literature often use terms like “environmental refugee” or “climate change refugee” that have no legal standing. The Refugee Convention limits the term “refugee” to people forced across borders due to persecution fears.

National laws under the UN’s Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement and international human rights laws should protect people moving within their countries because of disasters. People crossing borders due to climate factors don’t receive protection under the Refugee Convention.

The UN Human Rights Council stated explicitly in March 2018 that climate refugees don’t meet the “refugee” definition, calling them “the world’s forgotten victims.” People who cross international borders because of climate change lack the same legal protections as refugees or citizens.

The Nansen Initiative’s Agenda for the Protection of Cross-Border Displaced Persons in the Context of Disasters and Climate Change represents the most advanced platform on climate-induced human mobility. The agenda acknowledges that “international law does not address critical issues such as admission, access to basic services during temporary or permanent stay, and conditions for return.” Climate change continues to intensify, and experts predict the number of climate-displaced people will grow substantially in coming years, making this legal gap more concerning.

Sovereignty and the Externalization of Borders

Border control has evolved beyond traditional state boundaries. This evolution creates new power dynamics in international migration governance. Countries now “outsource” migration management to transit nations. This approach redefines control over human mobility while limiting legal responsibilities toward migrants.

EU-Turkey Deal and the Role of Transit States

The EU-Turkey Statement of March 2016 shows how destination countries utilize transit states to manage migration flows. Under this agreement, Turkey agreed to:

- Accept returned “irregular migrants” arriving on Greek islands

- Boost border security to prevent new sea or land routes to the EU

- Keep migrants who might otherwise move toward Europe

The EU offered these incentives:

- A “one-for-one” Syrian resettlement scheme (one Syrian from Turkey resettles in the EU for each Syrian returned to Turkey)

- €6 billion in humanitarian assistance for refugees in Turkey

- Fast-track visa process for Turkish citizens

The main goal was to reduce irregular crossings in the Aegean. The numbers dropped from nearly one million in 2016 to forty-five thousand in 2017. Yet the results fell short of expectations—only 2,140 people returned from Greece to Turkey under the agreement. Many Greek courts found that Turkey was not a “safe country” for returns, which made implementation difficult.

Visa Regimes and Passport Inequality Metrics

Passport privilege shapes border externalization and creates stark inequalities in global mobility. Not all passports give equal freedom of movement. This creates what some call “travel apartheid” between the Global North and South.

The Henley Passport Index reveals these gaps:

- Singapore and Japan lead with visa-free access to 192 countries

- UAE citizens enjoy unique mobility to 179 destinations without visa requirements

- Seychelles—Africa’s strongest passport—ranks just 24th globally with access to 145 countries

Visa policies work as “upfront prevention” tools, especially for distant origin countries. These policies create major ripple effects. To name just one example, Spain’s visa requirements for Ecuadorian travelers in 2003 cut immigration by 80%. This pushed migration flows toward other places like the United States.

Border Externalization in the Euro-Mediterranean Space

The Euro-Mediterranean region serves as a testing ground for border externalization policies. These policies involve “extraterritorial state actions to prevent migrants, including asylum seekers, from entering the legal jurisdictions or territories of destination countries”. Countries on Europe’s edges now handle more migration management responsibilities.

The European Trust Fund for Africa (EUTFA) funds these efforts. It claims to address migration’s mechanisms but often pays for security-focused border management projects. Tunisia received €37 million to “improve border control” and “manage migration flows”. This funding helped stop departures by making unauthorized movement illegal.

Critics say these externalization agreements don’t reduce arrivals long-term. Instead, they make migratory experiences more dangerous. Egypt and Lebanon’s stricter measures against asylum-seekers followed EU financial support announcements.

The European Commission now openly links migration control to its visa policies. A visa suspension mechanism introduced in 2013 activates when irregular migration flows from visa-free origins increase. This adds another tool to expand border externalization strategies that reshape international migration governance.

Diasporas, Dual Citizenship, and Transnational Influence

Diaspora communities create powerful transnational networks that shape economic development, diplomatic relations, and political identities beyond borders. These communities wield influence through financial flows, cultural connections, and political mobilization that affect both their origin and resident countries.

Remittance Networks and Economic Leverage

Money transfers show diaspora’s most visible influence by creating economic interdependencies between nations. Migrants send money to developing countries at rates between 70-95%, with annual flows exceeding $1.8 trillion. On top of that, about 90% of migrants buy products from their homelands, with those living in the United States spending around $440 per person.

Specific corridors demonstrate remarkable economic effects. Eight million Indian workers in Gulf Cooperation Council states transfer about AED 128.52 million yearly to India. Lebanese diaspora contributions reached $6.84 billion in 2022, which makes up 33% of the country’s GDP. These financial flows often exceed international aid and create substantial economic dependencies.

Diaspora investments and entrepreneurship help economic development in countries of origin. Several barriers to investment still exist:

- Limited infrastructure in telecommunications and energy

- Red tape and bureaucratic challenges

- Dual citizenship restrictions that make business ownership complex

- Scarce financing options for diaspora-owned small enterprises

Diaspora Diplomacy in India and Turkey

Countries now see their diasporas as diplomatic assets that can advance foreign policy goals. India made this official by creating the Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs in 2004 (later merged with the Ministry of External Affairs in 2015). Prime Minister Narendra Modi has emphasized the diaspora’s importance in promoting India’s interests abroad and encouraged wealthy Non-Resident Indians to invest.

Turkey’s approach to diaspora engagement tells a different story. Turkish authorities began recognizing their emigrants as a “diaspora” only recently, despite having over 50 years of migration history. Turkish government started using diaspora communities to boost its European Union membership agenda and improve public diplomacy in the early 2000s. Turkish-Americans, though relatively few in number, have gained considerable influence in advocating for Turkish interests in the United States.

Negotiated Citizenship and Political Allegiances

Dual citizenship policies reflect how national belonging has evolved in our era of transnational mobility. American citizenship laws don’t force people to choose between U.S. and foreign nationalities. All the same, dual nationals face complex situations where they “owe allegiance to both the United States and the foreign country,” which can create conflicting legal obligations.

Countries that allow emigrants to keep citizenship strengthen their transnational connections. They extend these rights for various reasons—keeping remittance flows steady, accessing human capital, or managing political dissent abroad. Dual citizenship for emigrants rarely faces political pushback, unlike immigrant naturalization policies that often spark heated debates.

Diaspora communities engage in politics through multiple channels. Indian-Americans have become “one of the most influential ethnic communities,” and they often lobby for policies that benefit India-U.S. relations. This influence can take the form of constructive engagement or potentially problematic interference, which raises questions about divided loyalties in political representation.

Migration Governance and Multi-Actor Diplomacy

Multi-actor governance has become the life-blood of international migration management. National governments, cities, and civil society now cooperate to shape migration policies. This creates new power structures that go beyond traditional state-focused approaches.

Global Compact for Migration (2018) Implementation

The 2018 Global Compact for Migration (GCM) created the first detailed framework for international migration governance. This non-binding agreement wants to help create “safe, orderly, and regular migration”. The agreement came after the 2015 refugee crisis. The first International Migration Review Forum in 2022 looked at the progress made and created a Declaration of Progress. This declaration renewed commitments toward shared migration goals.

Different regions show varying levels of progress. Stakeholders in Central America, North America, and the Caribbean made 17 pledges. These covered everything from protecting minors to adapting to climate change. Problems are systemic—notably after the United States pulled out of negotiations in 2017. They claimed the Compact would weaken national sovereignty.

Role of IGOs, NGOs, and Cities in Migration Policy

Cities play a vital role in migration governance. Urban areas host most economic migrants and refugees. Local governments provide essential services whatever the migration status. City leaders just need formal roles in international migration policy discussions—even if national governments abandon agreements.

International organizations work together through the UN Network on Migration. This network includes 38 entities led by a nine-member Executive Committee. NGOs also build mutually beneficial alliances with international organizations in areas like:

- Counter-trafficking and victim protection

- Assisted voluntary returns and reintegration

- Human rights advocacy and service provision

Migration as Soft Power in Bilateral Agreements

Migration now serves as diplomatic currency in international relations. European nations use financial aid and development projects as soft power. These tools help secure migration control agreements with African countries. This “carrot-and-stick approach” focuses on returns, readmission, and outsourcing border control.

Power imbalances define these relationships, yet transit countries utilize their strategic positions effectively. Turkey secured €6 billion in assistance and gained increased international recognition through its 2016 agreement with the European Union. Southern countries actively participate in global migration governance. They use migration diplomacy to gain influence and protect their citizens’ rights abroad.

Migration and Development Interdependencies

Migration and development share a complex two-way relationship that challenges what we typically believe. Research spanning decades shows our understanding has moved between different theories and findings.

Development Leads to Migration vs Migration Leads to Development

Traditional thinking suggests that economic growth reduces migration by closing the income gap between countries. The reality proves more complex than this simple view. Scientists propose what they call the “migration transition hypothesis” – a U-shaped relationship between development and people leaving their country. Countries see more people leaving as they develop until they reach a turning point. After this point, emigration starts to decrease.

This creates what experts call the “migration hump,” which peaks when average incomes reach $6,000-$10,000. People tend to move more at first because development gives them resources they need to migrate while raising their expectations. Recent studies tell a different story – they show that as incomes go up, fewer people leave their countries, even in shorter time periods.

The Win-Win-Win Model in Migration-Development Nexus

Benefits can flow to everyone involved in migration – the countries sending people, those receiving them, and the migrants themselves. Here’s how this works:

- Remittances: Migrants sent about $1.7 trillion back to developing countries in 2017. This amount was three times more than global development aid

- Knowledge transfer: People who return bring new skills and technology home, which helps create businesses

- Transnational connections: Migrants help build social and economic bridges between regions

This point of view shows a transformation from worrying about “brain drain” to seeing the potential for “brain gain”. Migration policy now blends with development plans, as shown by migration’s place in the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

Impacts of International Migration on Labor Markets

OECD countries had more than 15% immigrant workers in 2022, with nine countries showing numbers above 20%. Some sectors show even higher concentrations. Immigrants make up more than half the workforce in accommodation and food services across European OECD countries and the United States.

Studies show that migration barely affects native workers’ wages and jobs. The numbers tell the story – UK-born workers at the lowest pay levels saw their hourly wages drop by just half a penny each year from 1994-2016. Other immigrants, not native workers, face the strongest competition for jobs.

International migration reshapes global power dynamics and challenges our traditional understanding of sovereignty, citizenship, and governance. Migration patterns since the 1990s show unexpected trends. South-South migration has become more common than the widely assumed South-North flows. The growing gap between national sovereignty claims and transnational human movement calls for new approaches to migration governance.

Legal frameworks have evolved but still don’t deal very well with certain issues. Climate-displaced persons lack proper protection mechanisms. These shortcomings highlight the mismatch between today’s migration realities and older international frameworks that were designed for different times.

Border control now works differently as states exercise their power over human mobility. Destination countries extend their migration control way beyond their borders through visa systems, bilateral agreements, and financial incentives to transit countries. This approach creates unequal passport privileges that widen global mobility gaps. Powerful states can also limit their legal duties toward migrants.

Diaspora communities shape economies, cultures, and politics beyond national borders. Annual remittance flows exceed $1.8 trillion and create strong economic ties between nations. Many countries now see these international communities as diplomatic assets. This has led to new citizenship concepts that welcome dual loyalties.

Migration governance has shifted from state-only control to include cities, international organizations, and civil society groups. The 2018 Global Compact marks a turning point, though countries implement it differently based on their sovereignty concerns and national priorities.

Migration’s relationship with development isn’t straightforward. Development doesn’t simply reduce migration pressure. Research shows a “migration hump” pattern where development first increases mobility before reducing it later. This shows why we need careful policies that see migration as both an effect and cause of development.

Understanding these power dynamics helps create better migration policies. Future frameworks must recognize migration’s many aspects while addressing system inequalities. Migration will remain central to international relations. It reflects and strengthens global power structures while challenging traditional state authority in our connected world.